Branding is inescapable. If a Green party wants to stand out in a crowded field of competitors, they will have to have a strong idea of what their brand’s strengths and weaknesses are. Good branding can make the whole campaign a lot easier.

¶ Brands in politics

At its most basic level, the purpose of a brand is to act as a consumer behavior heuristic or psychological shortcut for consumer choice, allowing consumers to quickly and easily differentiate between similar products in any marketplace. Political brands are defined by academics as “political representations that are located in a pattern, which can be identified and differentiated from other political representations.” In politics, as in commerce, branding is essentially about recognition and expectation which allow people to make shortcuts (you might even call them stereotypes) in their decision-making process.

Here's some examples:

- In many countries the radical right pertains to ‘stand for the people’ but their policies actually hurt lower-class citizens. Here, they manage to ‘brand’ themselves as being something different than what they are, in order to amass more votes.

- Most of us are familiar with the concept of greenwashing where companies pretend to be more green than they actually are. Increasingly we can see something similar happening in politics. When climate change becomes a more important issue for voters, many parties start spending more attention talking about the issue, so that they are seen as a more ‘green' brand; regardless of their actual policies.

- The more vocal and visible a party becomes on an issue, the more people make that issue party of the party's brand. In Finland, when voters think about ‘education’ and politics, they tend to think about the Greens. However, in the Netherlands, voters tend to think about the liberal party (D66) when they think about education.

- When politicians and political parties are not seen as ‘authentic’ it has a detrimental effect on their electoral results. If a brand (image) does not coincide with what people see (actions), people lose trust and reconsider their vote.

Why would someone choose to vote for their local Green party over anyone else? Their reasons for doing so are part of what makes up the “brand” of that party, sometimes even more so than the party’s policies themselves. Is the party, and its politicians, seen as authentic, as an issue owner, as the solution to a problem, as a good representative of the voter?

¶ Brand Theory

A re-think of a green party’s brand will help re-think the whole strategy, answering many unanswered questions and clarifying things that might have been vague.

Before getting to some of the more practical applications of branding, it can be helpful to reflect on some of the underlying theory.

Please note, much of branding literature and theory comes from the world of marketing and corporate communications and as such, it may not seem immediately relevant to a political party. But by swapping out concepts such as “ideal users” for more applicable ones like “target voters”, we can already see how these theories can be helpful for us.

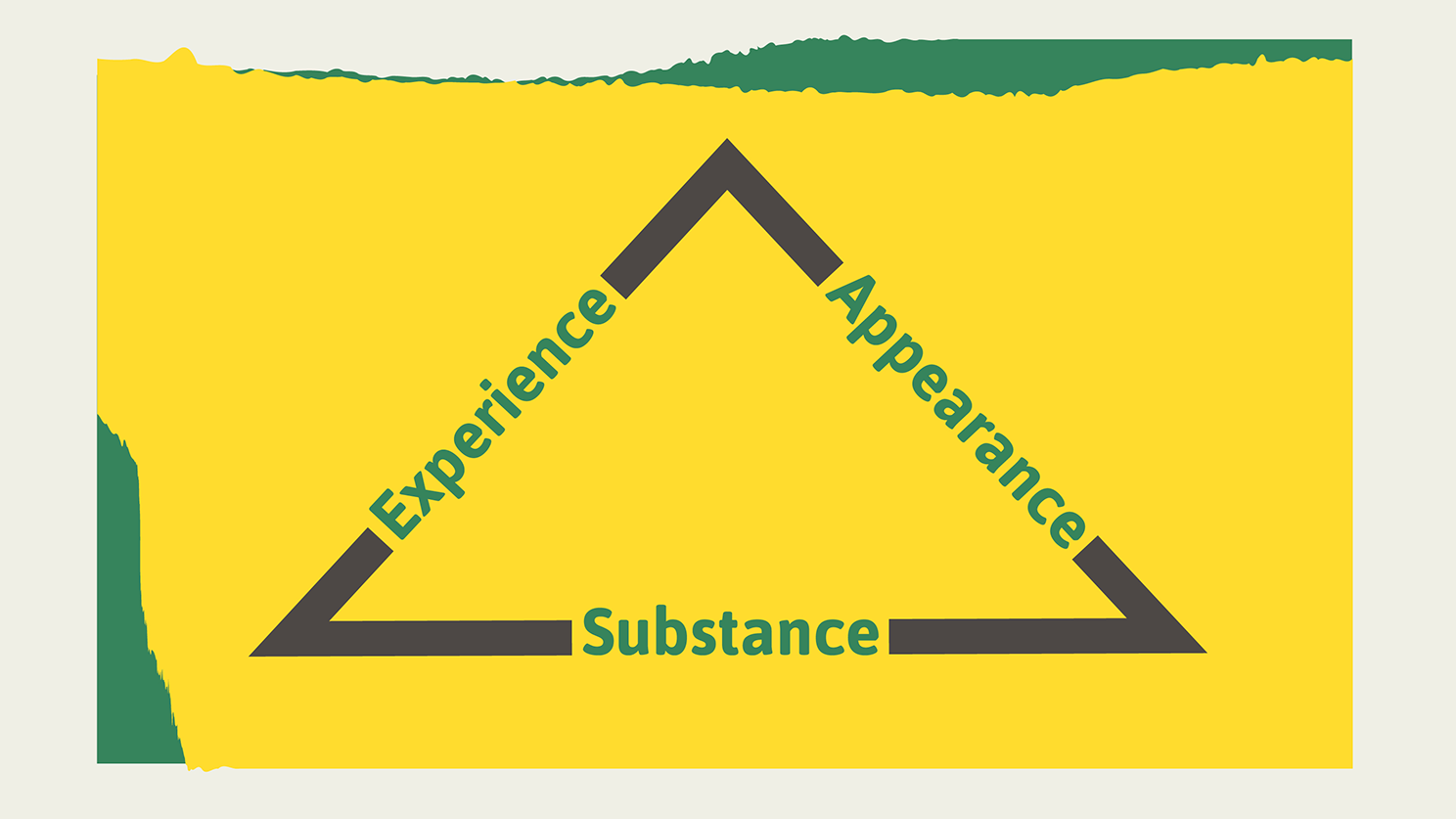

¶ 3 dimensions of a successful brand

A successful brand pays attention to these 3 dimensions:

- Substance

- The idea that guides the brand: the brand must answer some essential questions

- Appearance

- Stylistic and linguistic codes that can guide the user: a visual identity made up of a mix of ingredients that is constant and variable

- Experience

- A relationship between the brand and its audience at every contact point, also called the “user journey”

In a political context, the substance can be interpreted as the values and core policy goals of a party. The appearance is the visual identity of the party and the campaign materials more generally. And the experience is about how voters may first come to hear about the party and then end up casting a vote for it. Ideally, you want the image, the experience, and the substance of a brand to match (to be consistent). And, ideally, you want to continue this consistency over time and in any situation, so that you're creating a clear and strong ‘shortcut’ for voters.

These dimensions will come up again later in this article, under Brand Practice.

¶ Brand Platform

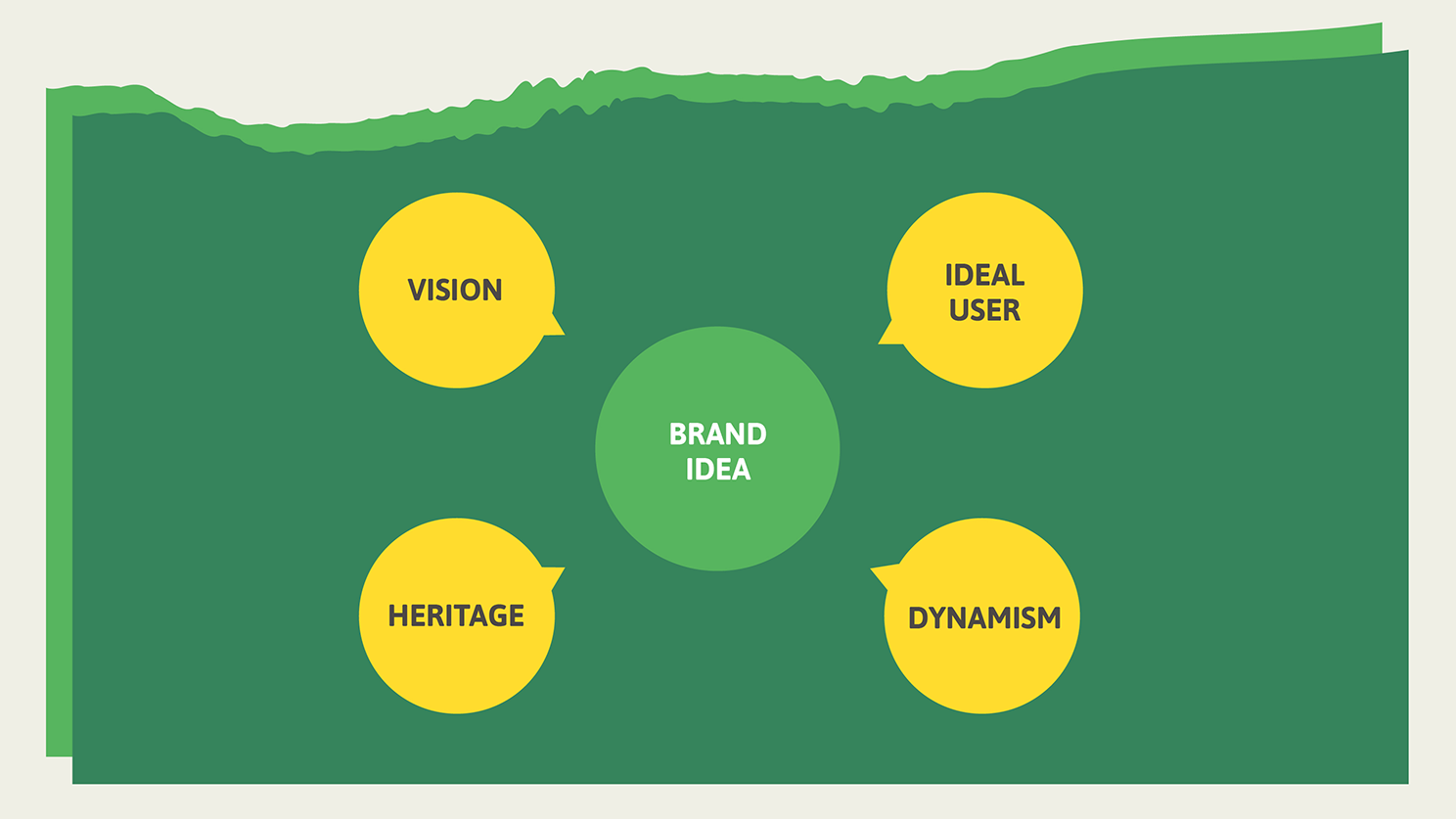

A “brand platform” is the best way to tell a brand’s story with a few well-chosen words.

It is one tool that defines and explains a brand’s fundamentals through simple phrasing. It is most useful as an internal tool, but some of the platform may still overlap with external communications.

The brand platform is made up of the following components:

- The idea that defines the brand

- A brand’s origin story, its heritage

- The brand’s vision on its market and its customers/users/voters

- A dynamism that allows the brand to stay relevant and keep moving

- The target audience or ideal customer/user/voter

The goal of this exercise is to come up with 2 or 3 words that summarise each concept, the more concise the better.

Here are some questions that can help with the process, rephrased to make sense in a political context:

- Brand Idea

- What’s the problem that the party solves?

- What’s the point of the party?

- What is unique about the party? Is it recognisable?

- Why do people want to vote for the party?

- Brand Vision

- Is the party known for a certain type of innovation?

- Can the party offer something more or better to voters than its competitors?

- Does the party have a certain quality that makes a difference?

- Brand Heritage

- What was the vision of the party’s founders? Why was it originally created?

- What is the iconic “product” or policy goal?

- Is there a founding myth? How do you romanticise the party?

- How is the party part of history?

- Brand Dynamism

- How does the party endure?

- How does the party keep innovating?

- How does the party expand?

- Target Audience

- How do we describe the ideal voter in one phrase?

- Does this fit every voter?

- Does that ideal voter naturally find their way towards the party?

- Mutual attraction: how is the party interested in its voters?

The process of establishing the Brand Platform can be quite difficult, especially if you are working in a party that doesn’t feel comfortable “branding” itself. A lot of these questions also point to structural aspects of the party and can provoke reflection on the wider strategy. This isn’t a bad thing, it can be part of a holistic approach taken when planning for a campaign. But a party that already has a clearly defined strategy will have a much easier time establishing its brand platform.

You can tell the difference between parties and organisations that take time to structure their branding and those that don’t. It is worth the effort to do it well and will prevent having to have many complicated discussions later on in the campaign when things get more intense.

¶ Brand Practice

Now that we have looked at some of the theory, it’s time to put it into practice. For example, if the brand platform is well established, practical decisions about the campaign become much easier to answer.

- Substance

The ideas that guide the brand: the brand must answer some essential questions in a way that makes sense to its audience.

- Appearance

Stylistic and linguistic codes that can guide the way someone interacts with the brand: a mix of ingredients that is constant and variable.

- Experience

A relationship between the brand and its audience at every contact point along the user journey.

¶ Substance

The substance is what makes up the bulk of the brand’s identity and it will inform the Appearance and Experience, so take the time to get this right.

The following components make up a brand’s substance:

¶ Narrative

The narrative is the summary of the brand in a way that makes the most sense to people. It’s the narrative that you tell yourselves as the motivation to work on the campaign, it’s the narrative that you tell voters to convince them to vote for you, it’s the narrative you tell prospective staff to encourage them to apply for a job. The narrative is key, and if it helps to view it in practical terms, it can form the basis of an “About” page on a website.

So what is the narrative of your Green party? Is it agreed upon across the team? Do party members and activists have a different narrative to the party compared to voters? If so, work out why.

See Campaign Narrative for more, but be wary that a party’s brand narrative is slightly different to its main campaign narrative. The brand narrative is more of an internal reference point, and it should be consulted as often as possible to make sure all other branding remains consistent.

¶ Context

The brand context is important to understand in order to place your party and the campaign in the current moment. The context is also about the political, social and economic situations that potential voters find themselves in during the campaign. The context flavours every part of the brand and how people understand it.

So what is the context that the party’s brand exists in right now? Is the party doing well? Are our typical voters in a good financial situation? How has COVID affected the election? Are climate politics relevant to voters’ everyday lives?

Every team member and volunteer should have an understanding of these contexts and how they affect the perception of the party’s brand. The context can also shift in an instant due to geopolitical events or the outbreak of a health emergency. Having a solid understanding of the context can allow the campaign to adapt and shift the branding to match the moment.

¶ Tone-of-Voice

The tone-of-voice is the way that the party presents itself in all its communications with prospective and current voters. What way should you write emails, what way should you speak on social media, what way should you tell candidates to talk about the party on TV?

What way should the party “speak”? Should you come up with internal guidelines? Are there certain ways that you should speak that reflect the world that we want to see? How can you be more inclusive in our language? What do your voters want to hear from you?

¶ Key Messaging

The key messaging of the party in a particular campaign should be an agreed-upon set of statements that become second nature to the whole team’s members and volunteers. They can then be used to promote the party in every social and professional interaction in a consistent and coherent way.

Messaging is not just a list of policy goals, it’s also the core values of the party expressed in an engaging way. This messaging becomes much easier to define once the Brand Platform (see above) is agreed upon.

¶ Appearance

The appearance of the party or particular campaign is the first thing that people see when they interact with it as a brand. Get the appearance right, and half the work is done. The appearance is shorthand for the rest of the brand.

Political campaigns benefit from thoughtful use of their visual identity. Smart candidates and parties coordinate their campaign materials with a unified theme. A successful visual identity can help make your name and message stand out amongst potential voters.

Green parties more or less share a lot of the same visual themes and symbols, but there is still a lot of room to explore new looks from campaign to campaign. It can be interesting to work around the limitations of established Green branding and find new innovative ways to present the party.

The following components make up a brand’s appearance:

- Logos

- This is often what first comes to mind when we think of a brand’s visual identity. While a brand can survive without a strong logo, a really good logo can come to symbolise everything about a brand in one quick-to-understand image. It can then be repeated on posters, social media, merchandise and on the ballot paper itself.

- Typography (fonts)

- A smart choice of fonts can do a lot of the work for you visually before voters even read the text itself. Is it modern or traditional? Serif or sans-serif? Light or heavy?

- A smart choice of fonts can do a lot of the work for you visually before voters even read the text itself. Is it modern or traditional? Serif or sans-serif? Light or heavy?

- Colours

- Green parties are often…green. But there is still a lot of room to manoeuvre here. A deep warm green is very different from a bright neon green. Like fonts, colours are a shortcut to your messaging before anyone even reads or watches anything from your campaign. Pair the green with a nice contrasting colour and give your visuals some flexibility to be able to adapt them to different uses.

- Green parties are often…green. But there is still a lot of room to manoeuvre here. A deep warm green is very different from a bright neon green. Like fonts, colours are a shortcut to your messaging before anyone even reads or watches anything from your campaign. Pair the green with a nice contrasting colour and give your visuals some flexibility to be able to adapt them to different uses.

- Symbols and repeated shapes

- Besides the logo, what other symbols and logos can be used to reinforce the brand identity? For Green parties, this is often a sun or sunflower, used in both literal and figurative ways. But you can also play around with different shapes that don’t have to mean anything in particular but do give off a certain quality that you want to share with voters. Sharp angles and straight lines will feel different to rounder shapes. Also, make sure to think about the symmetry and alignment of your visuals. Do you want to come across as orderly and organised? Or maybe a more scrappy and handmade quality is more appropriate.

¶ Experience

A campaign should adapt its branding to the probable “contact points” that someone will have with the party specifically and with the election process more generally.

- How will someone hear about the party for the first time?

- How many times will they encounter the party on traditional media during the campaign?

- In what way do volunteers interact with people at an event?

- How many get-out-the-vote emails will be sent out?

- What does the logo look like on the ballot paper or other official election material?

Sometimes the experience of a consumer brand can be linked to more tangible things like the softness of a leather shoe or the response time of the customer support helpline. But more often than not, it’s the things we just feel or think about the brand that give us the most impactful experiences. For a political party, it could be a combination of all the interpersonal interactions that you have with campaign staff mixed with the feeling you get when you share a post to your Instagram story and the pride you get when casting your vote.

Simply put, what is the brand’s “vibe”?

Good branding can smooth things out and address some problems without actually having to change the fundamental things underneath. This can be a bad thing, or it can be used to your advantage. Perhaps you are riding low in the polls after a disastrous TV appearance, but good branding could reassure the voter that everything will be OK regardless. This takes hard work!

¶ Summary

Branding is probably the most important thing to consider when drawing up your campaign plan. How is your party already perceived and how can you change that to benefit the goals of the campaign? Good branding ties everything together and transmits the whole messaging of the campaign in as efficient a way as possible. Good branding can often go unnoticed if it works, but everyone will notice bad branding. It is vital to treat branding seriously, and not let it turn into an afterthought.

Last updated: June 2022